This post is an extract from my talk Coding for Humans, you can watch it on YouTube and find examples on Github

A few years ago I worked on an European IoT project with many partners involved. Every party was developing one piece of a smart home setup: one of them was working on a washing machine that would automatically schedule their programs for when the electricity was less expensive.

I was curious of why did an appliance with such smart features was still using a (electro)mechanical knob to choose among cotton, synthetics and all other programs. Why not a fancy, colored touch screen? I asked the project manager in charge: the reason was that people are so familiar with the knob that they would not leave it for any other controller.

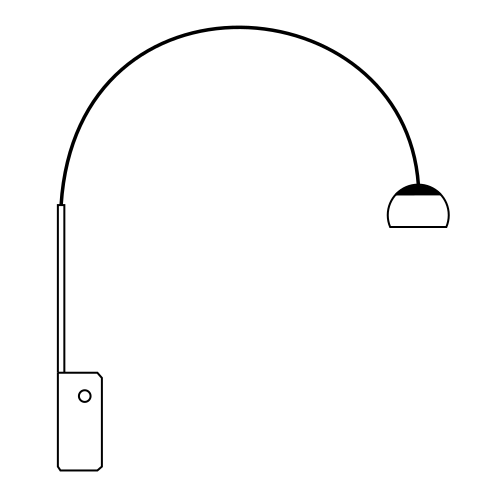

This is the moment I fell down into the design of everyday things rabbit hole. Let's take the lamp of my dreams, The "Arco" by Flos.

Designed by Castiglioni brothers, "it is characterized by a suspended spun aluminum pendant attached to an upright block of Carrara marble via a cantilevered arching arm made of stainless steel" (source: wikipedia). The marble base comes with a rounded hole. It is at the base’s center of gravity, guess why? Not for decoration, but to make it easier to lift the base by pushing something like a broom handle through it.

That was it: architect and engineers can both leverage empathy to design with the purpose of making life easier for end users, being it lifting a 65kg marble block or cleaning your shirts.

What if us, developers, used empathy while designing software for our users?

What about code

Who uses our code first? Who are first users of the code we write? Before compiling it, or bundling it, or interpreting it, it's other developers. In my case it's also myself, I cannot remember why I wrote a piece of code after a month I wrote it.

You might have heard that we spend way more time reading code than writing it. I worked with a lot of legacy code over the years and I struggled understanding it many times. Most of the time it was code written in the start-up hurry to deliver features. A few times it was code written with little shared context of the purpose or the decision thinking behind it.

Over the years the constant has been that all code becomes legacy code, eventually. Requirements change, features change, and the code must flow with it. This in mind, we can share as much context as possible to document our decisions and to help the next developer that will work on code we wrote.

Think twice about naming

Naming is hard, one of the hardest things in coding is giving explicit, well defined names to functions and variables. When naming a function I try to make what it is doing clear. Let's look at the following example:

class Rectangle {

constructor(w, h) {

this.w = w;

this.h = h;

}

calcA() {

return this.w * this.h;

}

}Can you guess what this code does? What about now:

class Rectangle {

constructor(width, height) {

this.width = width;

this.height = height;

}

calculateArea() {

return this.width * this.height;

}

}Now we don't need to look into calculateArea implementation to know it is returning the size of the rectangle.

Here is another example with constants:

const LETTERS = "qwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmQWERTYUIOPASDFGHJKLZXCVBNM";

const CHARS = LETTERS + "1234567890!@#$%^&*()_-+=[]{}|/?><.,;:";If you do not see CHARS assignment, could you guess what it contains? We can name it LETTERS_DIGITS_SYMBOLS:

const LETTERS = "qwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmQWERTYUIOPASDFGHJKLZXCVBNM";

const LETTERS_DIGITS_SYMBOLS =

LETTERS + "1234567890!@#$%^&*()_-+=[]{}|/?><.,;:";Prevent reading inner code

My rule is to use names that are explicit enough to prevent the reader from stepping into the implementation. The name or comments on top of it should tell the caller what it is doing. Let's use the rectangle from the previous example:

var rectangle = new Rectangle(3, 5);

rectangle.increaseSize(0.3);I cannot tell what increaseSize does. Jumping into the implementation:

class Rectangle {

constructor(width, height) {

this.width = width;

this.height = height;

}

increaseSize(percentage) {

this.width *= percentage;

this.height *= percentage;

}

}Turns out it is multiplying the rectangle's dimension by a percentage. We can call it scaleWidthAndHeightByFactor

class Rectangle {

constructor(width, height) {

this.width = width;

this.height = height;

}

scaleWidthAndHeightByFactor(percentage) {

this.width *= percentage;

this.height *= percentage;

}

}

var rectangle = new Rectangle(3, 5);

rectangle.scaleWidthAndHeightByFactor(0.3);Minimize function length

Let's take a look at an Adjust function for our Rectangle

function Adjust(rectangle) {

rectangle.Size = Size.S;

rectangle.HasError = false;

rectangle.IsSquare = false;

if (rectangle.Width >= 10000) rectangle.Size = Size.L;

if (rectangle.Height <= 100) rectangle.HasError = true;

if (rectangle.Width === rectangle.Height) rectangle.IsSquare = true;

if (rectangle.Width >= 20000) rectangle.Size = Size.XL;

if (rectangle.Height <= 200) rectangle.Size = Size.M;

if (rectangle.Width <= 300) rectangle.HasError = true;

}Changing the behavior of this function might feel like playing Operation. Given time is an option, the first thing I would do is refactoring it. To ensure I do not change the behavior, I would add a property base test. In this example I use fast-check:

import fc from "fast-check";

function test() {

fc.assert(

// create we random rectangles

fc.property(fc.integer(0, 30000), fc.integer(0, 30000), (width, height) => {

// initialize the rectangle with random inputs

let rectangle = {

Width: width,

Height: height,

};

// deep copy the rectangle

let rectangle_expected = JSON.parse(JSON.stringify(rectangle));

// adjust rectangle_expected with the old implementation

Adjust(rectangle_expected);

// new rectangle with the new implementation

Adjust_new(rectangle);

// check that all properties are equal across implementations

expect(rectangle.Size).toBe(rectangle_expected.Size);

expect(rectangle.HasError).toBe(rectangle_expected.HasError);

expect(rectangle.IsSquare).toBe(rectangle_expected.IsSquare);

})

);

}Now I can refactor the code, safely protected by the test. As a first implementation I can copy paste the old implementation. Then I can group together all the lines that impacts the Size property

function AdjustSize(rectangle) {

if (rectangle.Height <= 200) rectangle.Size = Size.M;

else if (rectangle.Width >= 20000) rectangle.Size = Size.XL;

else if (rectangle.Width >= 10000) rectangle.Size = Size.L;

else rectangle.Size = Size.S;

}I keep on with the other properties

function AdjustHasError(rectangle) {

if (rectangle.Height <= 100 || rectangle.Width <= 300)

rectangle.HasError = true;

else rectangle.HasError = false;

}

function AdjustIsSquare(rectangle) {

if (rectangle.Width === rectangle.Height) rectangle.IsSquare = true;

else rectangle.IsSquare = false;

}The end result is

function Adjust_new(rectangle) {

AdjustSize(rectangle);

AdjustHasError(rectangle);

AdjustIsSquare(rectangle);

}As long as my test passes, I can replace the old implementation with the new. I can eventually drop the test and the old implementation.

Top-down narrative

One last trick I use is writing code with a top-down narrative, starting from exported, public functions. Reading it feels like reading text:

class Rectangle {

// scaling functions

ScaleWidthAndHeightByFactor(scalingFactor) {

this.scaleWidthByFactor(scalingFactor);

this.scaleHeightByFactor(scalingFactor);

}

scaleWidthByFactor(scalingFactor) {

this.width *= scalingFactor;

}

scaleHeightByFactor(scalingFactor) {

this.height *= scalingFactor;

}

// scaling functions END

}In the end

In this article I shared some of the tricks that helped me writing more readable code. When in doubt, I ask for an external opinion to make sure I am sharing enough context with the code I write. Coming next, I will write about documenting code.